Eighteen Months of Solitude: Gabriel Garcia Marquez's Path to Immortality.

The story that had to be written.

Back at home late one night from a penniless job search, he heard the hopeless voice of his wife, Mercedes, telling him that she couldn’t give their two-year-old son a glass of milk because they had nothing to buy more food.

Without hope and without despair, in his mid-thirties, tired, frustrated, and with a son whining for understanding, Gabriel Garcia Marquez had to sit his child in bed and explain that they had no money for a glass of milk, that he was trying what was possible to find something to work at. Then, he promised his son that this was a low point of no return. And so the hungry child went to sleep quietly and didn’t wake up until the following day.

This was another night for Gabo. His dream? To be one of the greatest writers of the twentieth century. His reality? Infamous rejections, a travelled world, nothing to show professionally and nothing special that caught his mind other than finding a way to express more.

Coming from a humble childhood and searching for ways to escape his family constraints, raised by his grandparents and then reckless parents, his formative years were unenvied. Detached, he kept moving away from his hometown in Colombia’s countryside, Aracataca, to the big cities: Bogota, Cartagena, and Barranquilla. Struggling through life and only passionate about two things: writing and reading.

When he was young at school, he became an outstanding writer, devouring every book that crossed his way. He daydreamed during classes, writing satiric poetry for his friends and any possible article for the school magazine. Wishing for a future where he would be one of those authors people would read about.

Still, his passion was taking him nowhere. Close to his twenties and with high grades, he pretended to study law to satisfy his parents. Making little money from writing submissions, as long as he kept learning how to write better, he slept on benches, friends’ couches, unpaid hotel rooms, brothels, and on top of printing rolls in the newspaper office that gave him one of his first jobs.

He found ways to learn and study poor, travel the world poor, and get married poor. He dove into learning journalism and storytelling. He pivoted into cinematography to learn how to set dialogues and scenes together. Still dreaming, he met successful and unsuccessful people, lawyers, businessmen, renowned poets and meaningful lovers. He became intellectual and spirited but also penniless and lost. Even to the point where, after losing his job while he was in Europe, he found himself late at night walking on the bridge of Pont Saint-Michel in Paris, hungry and homeless, seeing a man walking his way with torn eyes, a sad face and a slow walk, figuring that he could have been himself going on the opposite direction.

Yet, over time, his hardships transformed his identity. At some point, he returned home to Aracataca to sell his family house; he claimed that it was “the most important trip of his life,” reconnecting with his roots and people from childhood. Having experienced life, he figured that most of his childhood stories were meaningful to him and likely to his writings. His struggles with relationships and life also taught him and made him create some of his works that are recognised today.

His ability to ask contemplative questions built to The Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor.

His almost homeless and disturbed love relationships in Paris realised No One Writes to the Colonel.

His time in Eastern Europe, London and Mexico gave solid ground to Big Mama's Funeral.

His stories from his grandfather and hometown built and rebuilt the narrative of In Evil Hour.

These stories were meaningful to him but not popular enough to others, whom some were still unsupportive.

“Storyteller?” Gabo’s demanding father once said, “Liar is what he is. He has been like this since he was young. He never is around when you need him.”

Time was telling him repeatedly that he should find something stable. Then, a few weeks after promising his son that he’d find a job soon, he connected with a reporter who was looking for support in editing a few Mexican magazines. Gabo suspended himself from his passion and wore his only pair of shoes with a detached sole to meet in his interview, and finally succeeded in being hired formally in a long time.

He breathed. He regained himself.

You can find balance while your dreams wait, but time never stops knocking on your doors and telling you it’s leaving. We accept it like Gabo seeing others achieving what he wasn’t able to: a renowned novel that could instead freeze time and make it stay there forever. Julio Cortázar crafting Rayuela, Mario Vargas Llosa delivering The Time of the Hero, and Carlos Fuentes with The Death of Artemio Cruz. The new Latin American generation of poets, the Boom generation, the ones living with William Faulkner or Ernest Hemingway.

This was Garcia Marquez, still pouring all his efforts pushing through while imagining the great fiction. Day and night, thinking, walking, breathing about it, dreaming of the next great literate idea, the one people would read in a worthy book in the years to come.

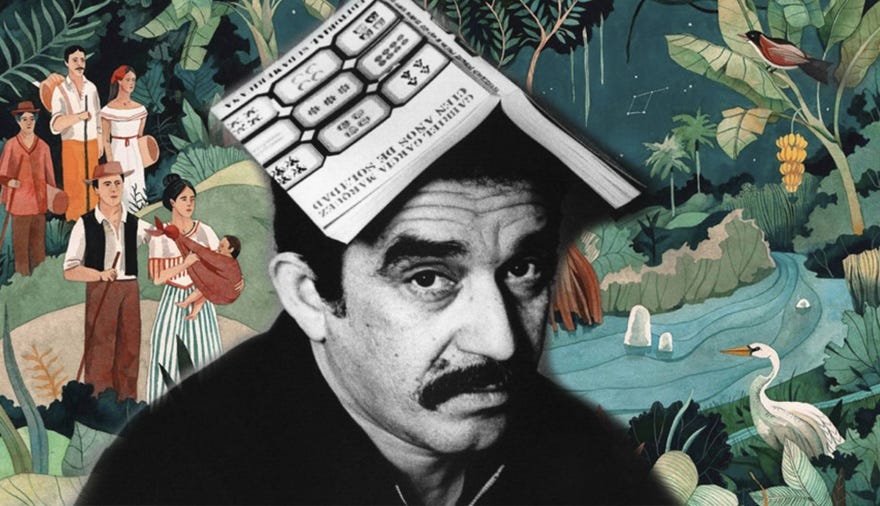

The story tells that it wasn’t long on the driveway one day while he was going on holiday with his family that the phrase, “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad…” came to him. The phrase wrapped in him a feeling, looking back at his childhood, his family, aunts and acquaintances, his grandad taking him to explore a big block of ice, the people he knew along the way, the story to tell. Giving little explanations to his family other than a map in his head made him stop the car suddenly and turn it around to go back home.

It became the beginning of One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Gabo said that when he arrived home the next day, he did what he usually did: sat with his typewriting machine, but this time, he didn’t stand up “for the next eighteen months.”

Within eighteen months, his sole focus and stress made him scared but excited, wondering how to close the story's next phrase and what could come next.

Within eighteen months, he was sequestered in his room, waking up to take his kids to school, returning home to continue writing, and just stopping to eat and read other works to curate his own.

Within eighteen months, he quit his job as he wrote blind but with faith. He felt how relief ran through multiple levels and in different directions, exploiting his efforts and angst from the failures and frustrations of an entire lifetime. By the time, he was thirty-eight and couldn’t afford trading responsibilities, but he still did for writing; it was an extraordinary bet for a family father.

In those eighteen months, everyone around him had something to do with the book he was writing. The magic of the novel and snippets of it were being shared around. He owed money to the butcher, the kid's school, and even some friends. At one point, their landlord called asking for the pending rent, and Mercedes asked Gabo how long it would take him to finish the novel, to which he said, “I still have five months to go.” The landlord agreed to extend the debt for five more months.

Amid his crafting, he felt he was building an immortal work when, one day, he was invited to a conference on Latin American culture and decided to take part of the manuscript to read it aloud. As he read on the illuminated stage, he remembered reading and reading and feeling the silence of the entire room; when raising his eyes to see the audience, he noticed the people on the first row with their eyes wide open, waiting for the next word to come. The air was suspended, like a fly wasn’t even moving. He felt his wife’s stare then, and he appreciated it all. The possibility to stay focused on his goal while she supported him in any way possible to keep them surviving that year. The ability to trust him with the beauty of working hard on something and seeing it happen.

They ended up selling their car to get money to survive those eighteen months. When the money was over, his wife started to sell everything else for another day: the TV, the fridge, the radio, the jewellery. Their friends shared any provisions to keep them surviving while Gabo was writing.

“Writing books is a suicide role”, he once said during those years, “no role demands so much time, so much work, so much consecration, in relation to the immediate benefits.”

When the novel was ready, he ended up with one thousand three hundred pages, which concluded into four hundred ninety. He accompanied Mercedes with what he said was a kilogram of paper to the postal office to send the finished manuscript to the editorial in Buenos Aires. On the counter, the service man said the delivery was “eighty-two pesos.” They only had fifty. They didn’t have a choice but to send the book's first half, go back home, sell the heater, the hair dryer, and the blender, and then send the other half.

Going out from the post office, Mercedes said, “Hey Gabo, can you imagine that the novel is bad?”

But the opposite happened.

One Hundred Years of Solitude was launched in Argentina on May 30, 1967. It cost two dollars, and publishers estimated sales at eight thousand copies in six months. The book has sold over fifty million copies worldwide, making it one of the most sold books in history.

Initially, he was already noticing the fame. Still, one of his gracious points was when he visited Buenos Aires around the same time and one morning found a woman with a book copy in her shopping bag between the groceries while having breakfast at a random place.

Not only renowned by Fuentes, Cortázar, and Vargas Llosa, but the novel made the world stage and met the most outstanding personalities from heads of government, influential people of the time and legends like Pablo Neruda. Gabriel García Marquez won the Nobel Prize in Literature from this experience; his life changed forever.

Despite the struggles, despite his setbacks, and despite poverty, Gabo made it. He found grit amongst it all. We all have it. Sometimes, it doesn’t come in how we wish it or leads us to the initial goal we crafted. But what matters is trying and trying hard. It can be a lifetime of discovery and finding your life task. Of making mistakes, of repeating them, on learning. Deepening your roots and understanding your unique purpose, finding the right novel, act, or legacy to give, the one that depends on you and only on you. Like Gabo, finding awe, returning home or going out from it, and puzzling his life story. And sometimes, it can be as challenging as eighteen months or more, pouring your efforts into something, evading distractions and fixing it along the way.

As author Robert Greene mentions in Mastery, once you find your life goal, the gracious part is to attach yourself to it as firmly as possible. To hold it with all your heart. It took Gabo to be constantly obsessive and emotionally committed to his dream, to reduce his ego, and to find ways to experience the life set for him, not the one he desired. Yes, maybe you need to do something to hold you in the meantime as you try to achieve your side hustle, or perhaps you need to allow yourself to do more research and find, or maybe it is just not the right time for you yet.

But once it is the right time, once you find that life task, you have to keep going. In the long run, that will make your life precious and give you infinite energy, even as time keeps knocking.

Right after finishing the novel, he wrote a letter to a close friend, saying, “When you have something that haunts you, it builds up in your head for a long time, and the day that it explodes, you either have to sit with the typewriter or run the risk of choking your wife.”

It’s a story of a lifetime. It’s a story worth repeating.

Sources

[1] Gabriel García Marquez: A Life - Gerald Martin

[2] Mastery - Robert Greene