Is this the best you can do?

The creator trap: doing your best work or not doing anything at all.

During the 70s, Henry Kissinger's assistant had the strenuous task of preparing speeches for the then-US Secretary of State. Imagine this daunting task of serving a world-leading speech writer, with America in a domino battle of relationships between China, the Cold War, and the Vietnam War.

Kissinger asked his assistant to prepare a speech covering these global themes. The speech was submitted for review, and Kissinger proceeded to ask,

“Is this the best you can do?”

The assistant replies, “Henry, I thought so, but I’ll try again.” Returning to the task, he changes, revises the speech, and submits it again. Kissinger replies the next day,

“Are you sure this is the best you can do?”

The assistant replies, “Well, I really thought so. I’ll try one more time.” This process goes over for more than a week, and after the ninth submission, Henry replies,

“Is this the best you can do?” to which the exhausted and frustrated assistant replies, “Henry! I’ve beaten my brains out – this is the ninth draft! I know it’s the best I can do; I can’t possibly improve one more word!!!”

Kissinger replied: “Fine, then I guess I’ll read it this time.”

You would consider this a usual Kissinger drill. Every word mattered to the political titan, and he only thought a speech was done once it was revised multiple times. The biographer Walter Isaacson writes that he also demanded the same level of perfection from his staff and colleagues.

On the one hand, the lesson here is that we all inherently put psychological barriers in our way of doing our best work, and we need to identify the Kissingers in our lives who can help us scale over those walls to a higher level. But on the other hand, the opposite is true: In a world where we translate our versions of Henry Kissinger to intimidate us, we can freeze ourselves from sharing any work.

I type this because I am not a famous writer, a precious painter, or a talented actor. I am an average person in his mid-30s who is figuring out what drives his meaning and connecting with others who do the same. I intend to start writing publicly, but I am more scared than excited because of the commitment it takes. We can think about this about crafting anything else too, following the questions below -

Will I [add any action] well enough?

Will I [add any action] consistently?

Will I [add any action] on interesting stuff?

Will this impact the perception in my professional career?

Will my colleagues and friends say something about this?

More often than not, I step back, thinking of Jonathan Haidt saying that people don't communicate with each other on social media but rather perform for each other. And then, when I decide not to pursue any of this craft, I remind myself that we are held back by the opinion of people that we don’t care for anything else.

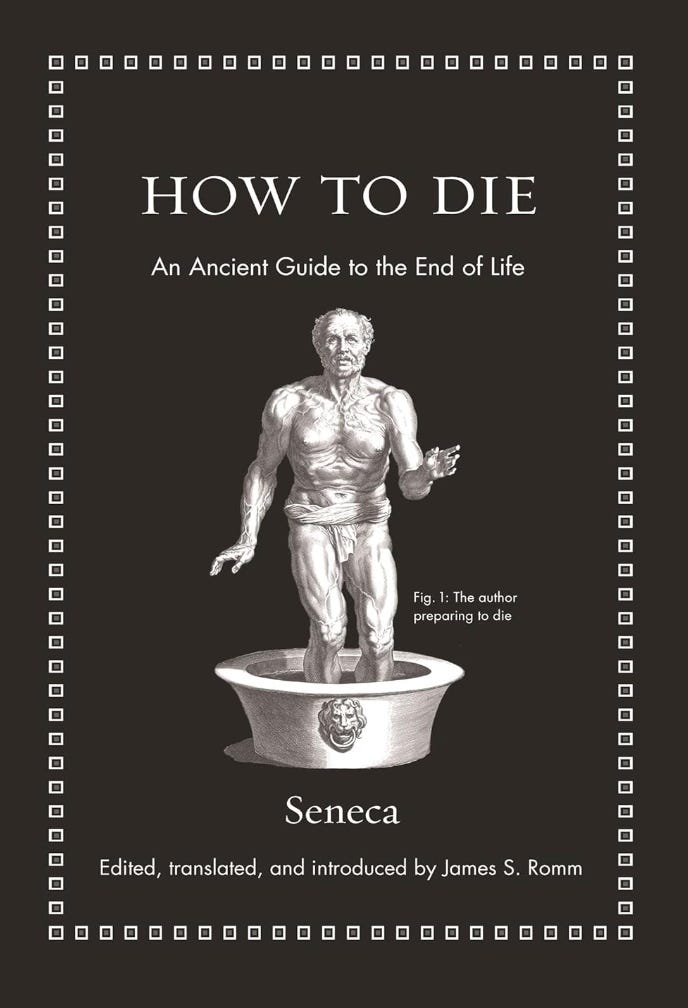

I have many reasons to start writing, and as you can also see, there are many reasons to fear doing so. After all, it is easy to regret not having spent more hours crafting something before. Had I pursued my life differently, my outcome wouldn’t have been living where I live, meeting whom I know and doing what I do. As I type frenetically from my desk, proud of what I have achieved with my linear thinking, I catch myself quoting Seneca in his essay On the Shortness of Life, saying, “It is not that we have a short time to live, but that we waste a lot of it. Life is long enough, and a sufficiently generous amount has been given to us for the highest achievements if it were all well invested.”

How short could life be to wake up and do more hard and meaningful things?

This is to say that one of the things I enjoy doing the most is reading and sharing what I read. It fulfils my soul and energises my body; it drives my dopamine and feeds my place in society. My biggest heroes are authors who defied expectations and surpassed lives full of obstacles and financial constraints and, in doing so, shared the best ideas to help others do the same. Reading and writing are opposite sides of the same spectrum, so why shouldn’t I try to write?

You may think about your tastes and instead, consider cooking. Others like to sing and play an instrument. Others like politics and caring for social causes. Others do hike and nature. Others share arts, theatre or Netflix. Others spend most of their time caring for their community or their street. Others spend their lifetimes taking care of their families or close ones. These are all sides of a spectrum; they all have an opposite side, a creative and contributor side. What are you not trying to share? What do you think you’d like?

Famous musician Brian Eno describes the side of the creators as part of the “scenius”, an ecology of talent—a community where people open themselves not necessarily about how smart and talented they are but about what they have to contribute. The ideas you share, the quality of the connections you make, and the conversations you start. I like that—a space where we all share and learn from each other.

I intend to say that we might be daunted by a Kissinger in our lives who is preventing us from submitting our best selves or helping us push our best work. We should find those characters and be aware of them. Dance with or avoid them; otherwise, what do we have as an alternative?

Is this the best I can do? Maybe. For now. There are thousands of ways and combinations that I could have used to write this, but I am satisfied with choosing this one.

Best-selling author and writing teacher Anne Lamott would point her finger at all of this and say is this your “Shitty First Draft” or is this your final version? And I would say I don’t know; it might feel suitable for someone to read it. Author Austin Kleon leans towards promoting all of us as “Amateurs.”

Those willing to try everything and share results.

Those not afraid to fail, make mistakes and look ridiculous in public.

Those who are in love, obsessed, spending a lot of time thinking out loud about something.

Those who know the real gap is between doing nothing and doing something.

We might strive to be amateurs, but why do we care about doing this at all? “We write to understand life”, as Annie Dillard says, allowing others to connect equally. We might say the same about sharing our ideas in any other form, about any other thing. Steven Pressfield was introduced to the idea from Homer’s Odyssey of invoking the muse and becoming this vessel for creativity. Imagine that! Being a vessel. In his book Perennial Seller Ryan Holiday argues that he writes…

Because there is a truth that has gone unsaid for too long

Because you’ve burned the bridges behind you.

Because your family depends on it.

Because the world will be better for it

Because the old way is broken

Because it’s a once-in-a-lifetime-moment

Because it will help a lot of people.

Because you want to capture something meaningful.

Because the excitement you feel cannot be contained.

Because, because, because. Can this be impactful? As Nicholas Christakis and James Fowler said, everything we say or do ripples through our social network, creating an impact in three degrees of influence. Hence, any positive emotions, such as happiness and hope, can be traced and spread through our networks: Our friends, our friends' friends, and even our friends’s friends’s friends. That is very powerful, isn't it?

Even by doing this act, facing the fears and finding your voice through making a craft, you might change how you spend your time and with whom you spend it. But it may also push people away from us. We could be compelled to make painful choices when we intend to grow, share what we love, and try to live a life closer to ourselves and the world.

In a world where expectations freeze us and we doubt our efforts, the brave way to flourish is to retain an amateur’s spirit and embrace uncertainty and the unknown. As Steven Pressfield in The War of Art points out, by fighting this resistance, “we will have to choose between the life we want for our future and the life we have left behind.”

Sources

[1] Kissinger: A Biography by Walter Isaacson

[2] On the Shortness Of Life by Seneca

[3] Show Your Work by Austin Kleon

[4] Perennial Seller by Ryan Holiday

[5] Bird by Bird by Anne Lamott

[6] Three Degrees Of Influence by Nicholas A. Christakis and James H. Fowler

[7] The War Of Art by Steven Pressfield