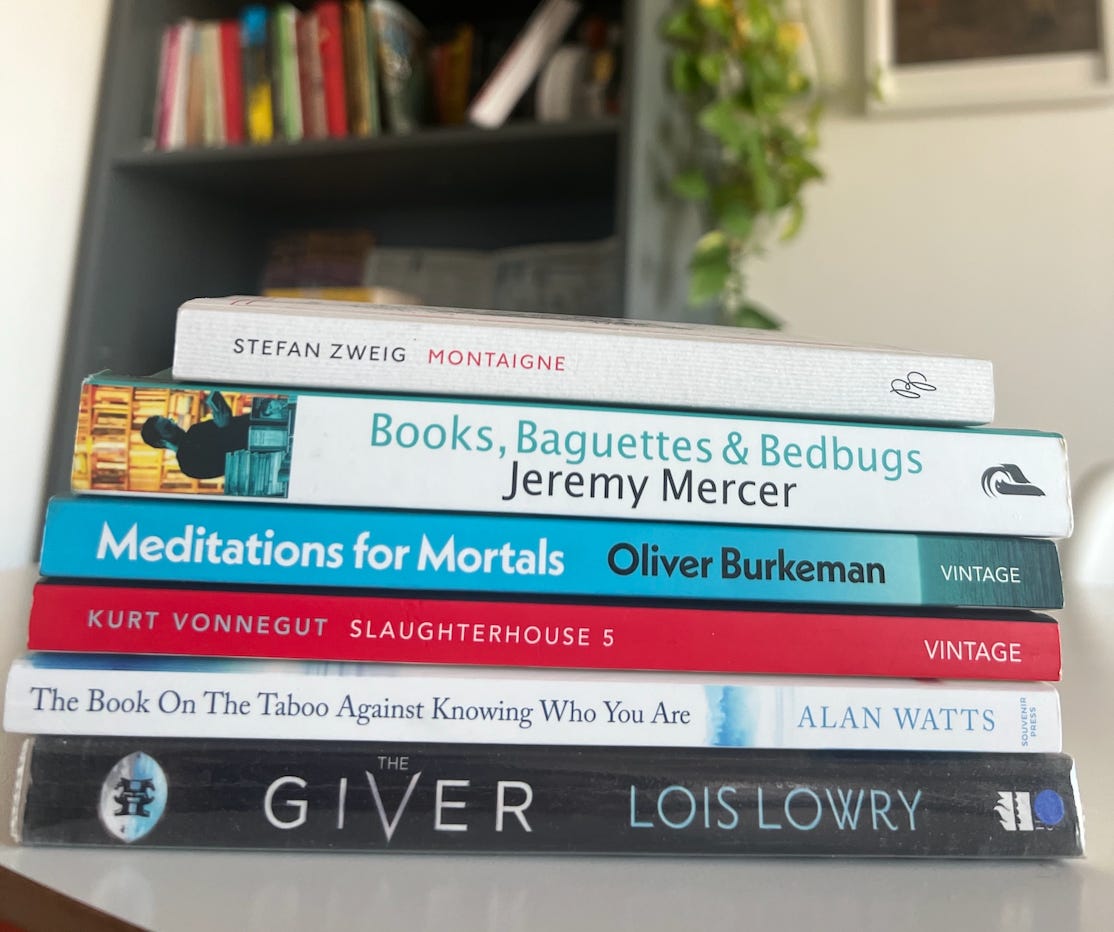

Reading List for August 2025

"He who thinks freely for himself, honours all freedom on earth." - Montaigne

We live in the world our questions create. But how hard is it to make a good question? Sometimes it can take us many steps to get there, stumbling, rushing, repeating ourselves. Or sometimes coming so close, to questions that are right in front of us, or on the tip of our tongues! But we fail to recognise them. Sometimes, becoming blind altogether, even all the way getting tired of doing the opposite: giving opinions… But using our fingers to count the questions asked. Winston Churchill pointed at this once by saying that people "occasionally stumble over the truth, but most of them pick themselves up and hurry off as if nothing ever happened.”

Isn't it fundamentally dangerous? To spend your life away, in the effort to question… right? Yes, awfully risky, awfully slow, terribly disappointing, to our ego, to our dreams, to our expectations… To not rush. To just ask better, next time.

But isn't it also fundamentally human? To seek, to build, to rebuild, to find ways through. To take more time. To be imperfect in your search, altogether, but at least to search for something.

It might be that you spend your whole life without getting where you wanted… But perhaps that’s what you needed, to finally get somewhere else. Somewhere different. Maybe not what you were expecting. Maybe, and just maybe, worthy of experiencing. Living. Breathing. Learning. Making something better out of where you were at. “Most of life is a search for who and what needs you the most,” said entrepreneur Naval Ravikant.

What to do, then, if you want to live in a world that’s at least close to the one you've always imagined? What to make, if you want to ask better questions? I can only say that I have one part of the answer for you. It’s three words: read, read, read. To keep an open mind and find ways to learn new perspectives. To give up on a fixed mind and be fluid in a text of possibilities. To navigate and debate all writers: the dead and the ones living. Those who spent their lives away trying to question right. Following their path of thinking and placing the next stone on the way. How cool it is to be able to find a book and to exercise its ideas, and maybe, just maybe (why not?) on a daily basis? Here are the ones that made my reading list for this month!

The Giver by Lois Lowry - When this book was released in 1993 it was partially banned because of its reference to sensitive themes like euthanasia, suicide and infanticide. It later became a bestseller, though I initially missed the deeper reason for its fame: the author’s intention of showing what it’s like having a totalitarian authority controlling the community over their sense of individuality. Lowry shows us what a world would be like if it was in black and white, with someone else choosing what you eat, what you speak, what you know about history (imagine—no memories from the past!), and what your purpose in life is. Identity loss. Monotonous living. Rules following, and you won’t be punished. The irony is that one person serves as the 'memory' holder, someone that has access to all the things and thoughts that the community cannot access, so that there can be proper advice against mistakes that the authority can commit. But what if the next memory holder decides that’s enough? That everyone needs to see the colours, and have the right to choose? This book is a light read and I highly recommend it!

The Book on The Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are by Alan Watts - Written in 1966, this became one of the most meaningful books I've encountered this year. I found Watts by watching the movie Her (2013); he appears as another AI subject somewhere in the middle of the movie and his role was to discuss and make sense of the reality of artificial intelligence as an individual. Watts represents one of the first authors to bridge Eastern thought into the Western world. This book touches various important themes such as our metaphysical sense of reality (whether as a biological being or a system of electronic patterns, which we already are in some ways), the sense of our ego, the need for an opposite, and the double-bind game that we play in society, losing ourselves in the process: “The first rule of this game is that it is not a game.” Watts describes and continues, “everyone must play. You must love us. You must go on living. Be yourself, but play a consistent and acceptable role. Control yourself and be natural. Try to be sincere.” Yet, it is because of this double-bind game that we have scrubbed the world clean of magic, and by trying to find meaning across tribes, we have become invariably divisive and quarrelsome. In this sense, along an enriching view from different angles, Watts urges us to develop our self-knowledge, our own perspective and expressions, and to experience our actions and those of others with as much contemplation as possible.

Slaughterhouse Five by Kurt Vonnegut - This is a deep and at times painful work of fiction written by one of the classic American authors. Vonnegut makes allusion to his own time as a prisoner of war during the Second World War, and further release and coming back to a normal civilised life in America. The protagonist makes decisions without emotion, suffering from being 'unstuck in time' and traveling across different ages of his life while also being abducted to an alien planet. With often very descriptive scenes of the war and how American prisoners were being captured and taken by the Nazis, the author makes allusion to the often overlooked psychological reality for those who are in imprisonment torture conditions and suddenly are not. “How nice—to feel nothing, and still get full credit for being alive.” And also at some points to the changes in fortune, “why you? Why us for that matter? Why anything? Because this moment simply is. Have you ever seen bugs trapped in amber?”

Meditations for Mortals by Oliver Burkeman - Already one of my favorites this year. I am a big fan of the writings from Burkeman and I subscribed to his newsletter “The Imperfectionist”. His previous book " is a book that I recommend to anyone who wants to grasp their own concepts of happiness by using philosophy and mortality as tenets. In his new book, Burkeman divides his writing into four blocks, and invites us to read one chapter per day for four weeks and be contemplative about their meaning (I read them in one week). The blocks are split first on being finite; second on taking action; third on letting go; and fourth on showing up. Although the concepts might sound repetitive for those of us who have been reading long lengths of modern philosophy contents out there, I learned really good perspectives for each block. There is this sense of feeling much better with myself after I read something from Oliver Burkeman. I praise his work and I highly recommend it to everyone!

Books, Baguettes & Bedbugs: The Left Bank World of Shakespeare & Co by Jeremy Mercer - I learned about this book while visiting The Gently Mad Book Shop & Bookbinder in Edinburgh. The owner recommended it to me as I was telling him how fascinating it would be to have a bookshop like his; everything it must have taken him and the experiences he has grown into. “You should read Books, Baguettes & Bedbugs” he said, and I immediately ordered it. The author, Jeremy Mercer writes his experience as a journalist in the beginning of the new century, escaping his home country (Canada) into Paris; quickly running out of money and looking for a place to sleep, when he found out the bookshop Shakespeare & Co and learned that this quirky place hosted writers to sleep over for free. Under the Bible tenet “be not inhospitable to strangers, lest they be angels in disguise,” the bookshop founder, George Whitman, quickly welcomed Jeremy and together with a group of nomad authors, with no money and high dreams. The story walks through the fascinating background of George and his travels, the dreams and challenges of each guest, the spirit and management of the place, and its roots from the original bookshop Shakespeare & Co by Sylvia Beach (Link to her own book here). Sylvia was the only publisher who trusted James Joyce's work Ulysses and published it in 1922, as well as a mention of other famous authors of the era that passed by, such as Ernest Hemingway. The original bookshop was supposedly closed during WWII as the Germans were concerned for the creative nonconformity and Sylvia’s undisputable stand against totalitarianism in art. With my girlfriend, I had the chance to visit the bookshop this past month and it’s wonderful how they still preserve many of the facets from the time of this book (25 years ago), but there was mixed feedback on whether they’re still letting people sleep in for free.

Montaigne by Stefan Zweig - Ryan Holiday's recommendation led me to this book. Stefan Zweig was capable of describing in this short biography how the high-born Michel de Montaigne, struggling to meet the expectations from society, decided to leave behind his life of wealth to take refuge in a tower with his books and his thoughts for over a decade. In the process, he constantly read and wrote his famous essays, he discovered his own maxims and those which are so hard to attain, even for himself: to seek his interior self, that one which Goethe calls the “citadel”. On the beams of the ceiling, he paints fifty-four Latin maxims, so that wherever his glance falls, it finds a sagacious and soothing word. Only the final one is in French, the famous “Que-sais je?” or What do I know? To which he always tries to set as an end maxim across his opinions. Stefan Zweig makes wonderful allusions to the essence of Montaigne essays, appreciating the fact that he discovered them twice, once when he was very young in his adolescence, and secondly in the last stage of his life. “The outside world can take nothing from you and cannot unhinge you, as long as you do not allow yourself to be disturbed…For one of life’s mysterious laws shows that we only notice the authentic and essential values when it’s too late: youth, once it has fled, health, at the moment it abandons us, freedom of the soul, that most precious essence, at the very moment when it is taken from us, or has already been taken.” The sad part though, is that consumed by despair over the Second World War in Europe, and after carefully taking some of Montaigne’s words, Zweig and his wife took their own lives with an overdose while living in Brazil in 1942. It's a shocking and tragic irony for someone who wrote so beautifully about finding inner peace.

I'd love to hear your thoughts on these ideas. The best books you can read come to you through word of mouth, so if you know good titles that relate, please share them! If any of these resonate with you, pass them along.