Reading List for December 2025

On home, history, and who we become.

Have you had that feeling when you come back home over the years, and you don’t recognise the place the way you used to? Colours, smells, spaces, that feeling and narrative of the past that became absorbed and transformed by the present? What is it that we really call home, then? Is it a place, a person, a time? What if none of them exist anymore? Also, what does that mean for who we are? What does it mean for the country that you came from?

Can you call yourself from one nationality even though you were born there but left more than ten years ago?

An African, North American, Atheist, but Christian for the past 3 years?

An Indian, Russian, and Muslim?

An Arab, South American, British, and born in a religious family, but not so religious anymore?

Is there a mould for any of those? Are they all immigrants? Could they recognise themselves by their country of birth? Or are you the product of all the places and times? The result of many events, emotions, people and dialogues together. The opposite of this is fitting a mould, an inauthentic self, shape, or label.

What about the beliefs? Spiritualism or religion plays a large role; it’s what makes people connected… or disconnected. I keep reminding myself that one cannot have religion without faith, but one can have faith without religion. Traditions, celebration dates, ways of thinking—It makes me think how urgent it is to explore ourselves by looking to the past to see our present. I can’t call myself one thing or the other; I cannot think I am pro one thing and hence I need to be against the other. The world needs a richer dialogue, not an either/or, but rather a both/and. Between our pasts, assumptions, and learnings—this month I’m exploring how geography shapes global politics, one philosopher’s reflections on her family journey through communist Albania, and a Southern classic about alienation in modern life.

The Moviegoer by Walker Percy - This book tells the story of a veteran who returns home from the Korean War and loses his sense of meaning, rejecting the “everydayness” of life. Friends, love, purposeful work—he decides to trade it all for at least “five minutes” from the wonder of TV and dating a new woman every chance he gets. He notices that not searching for something is to be in despair. But on the other hand, there are those who, in a constant search for entertainment, finally find no one and nowhere. Or how people around him keep saying that they believe in the uniqueness of the individual, but that those are far from unique themselves. Originally published in 1961, this book relates to our alienation in the modern age, weighing our decisions based on short-sightedness rather than what’s hard but morally correct and truly being alive. Percy touches on philosophical and existential concepts from his Southern Catholic background and from the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, in the fulfilment of the individual spirit. I enjoyed how the different family members pull the veteran toward their own perspectives on life. “Have you noticed that only in times of illness or disaster or death are people real?” his fragile cousin Kate tells him at one point, “I remember at the time of the wreck - people were so kind and helpful and solid. Everyone pretended that our lives until that moment had been every bit as real as the moment itself and that the future must be real too… In another hour or so we had all faded out again and gone our dim ways.” This is widely considered Percy’s masterpiece, full of classic writing, Southern tones and a call for one’s own authenticity.

Prisoners of Geography by Tim Marshall - I wasn’t aware that a million people died during the displacement of citizens between India and Pakistan when the British decided to withdraw their empire and partition the countries in 1947. I also wasn’t aware that the isolation Africa has experienced over its history is largely due to its geographical challenges and impractical rivers. Or how the European Union holds France and Germany together economically to avoid another world war. Or how Egypt, Syria, and Jordan are suspicious of Palestinian independence due to their own territorial claims. Or that the South China Sea is having one of the highest tension crises in history due to its complications with Taiwan, while the US holds a military alliance with most of the area, a military capability that China is now building. Or the cycles of American foreign policy embodied in Teddy Roosevelt’s maxim to ‘speak softly and carry a big stick’. Marshall has participated in broadcasting world events for the BBC, Sky News, and other international news outlets, and in this book, he provides an insightful overview of how geography shapes global politics as he walks us through ten maps of the world. It also gives you an overall context on religious tensions and interpretations across the world, and how, for example, the intelligence services in London reported that in 2015, more British Muslims were fighting in the broader Middle East region for jihadist groups than were serving in the British Army. The book could always feel outdated or biased due to the changing geopolitical landscape and Marshall’s Western point of view. Still, nevertheless, this is one of those books that makes you wonder how strongly you believe things you know so little about, and will help ground you better if you are looking to develop a global perspective.

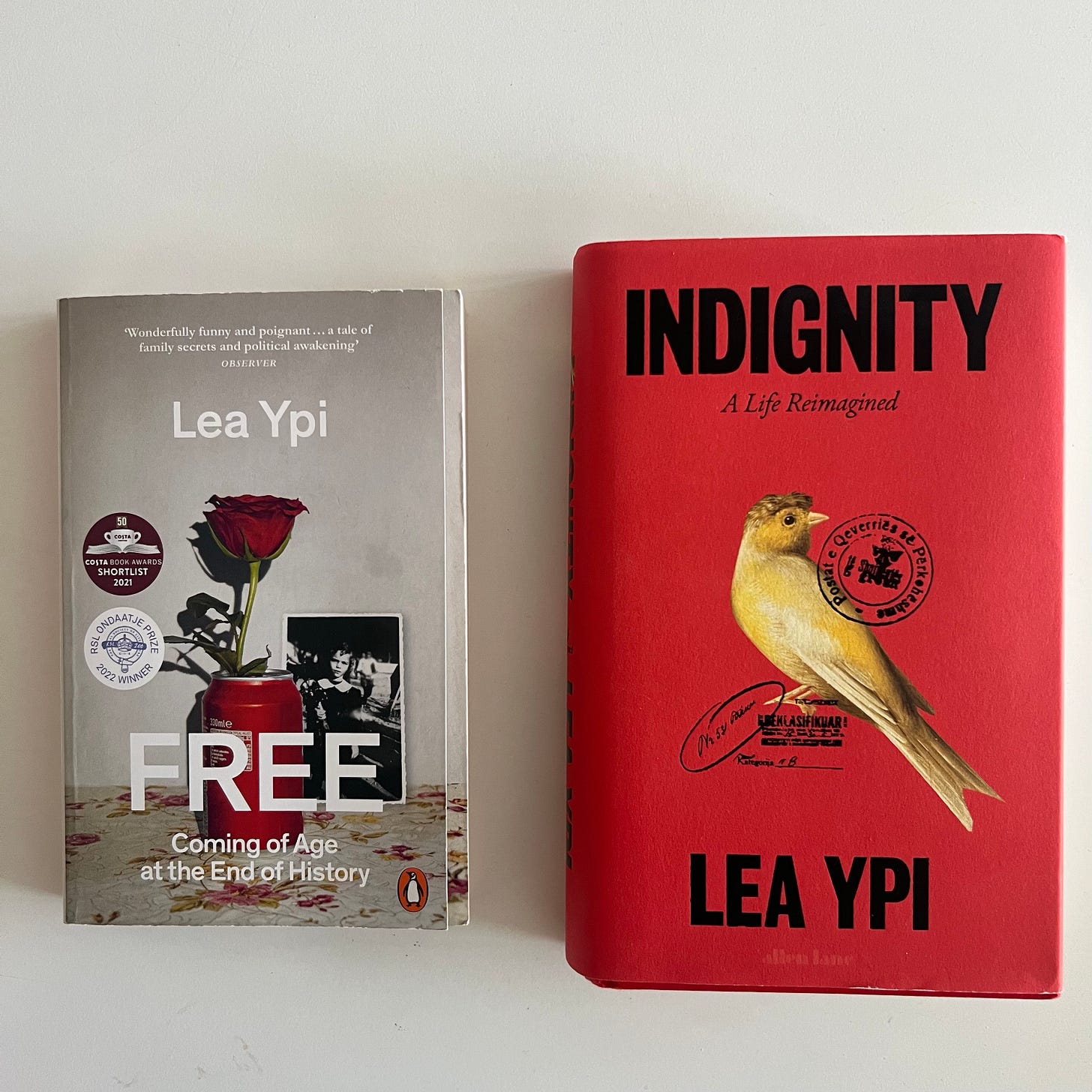

Free: Coming of Age at the End of History by Lea Ypi - The genuine excitement of a child is nothing you can compare: riding their first bike, a novelty toy, the joy of new encounters. For the young Lea Ypi was being convinced that there was nothing better than communism. She woke up “every morning wanting to have communism faster.” It was the 80’s and it was Albania, and her school, friends, and everything around her would convince her so; everyone but her family, who, for silent reasons after decades of the regime, couldn’t tell her their honest opinion for fear of being prosecuted. In this book, Ypi walks us through the perils she faced during her childhood, from the mysticism surrounding their country’s leader, Enver Hoxha, to long queues for the most basic things like cheese or kerosene (have you heard about these urban crises recently, somewhere else, some other times?). The subtitle, “coming of age at the end of history,” continues with Ypi’s broken innocence and revelations after Albania became a multi-party system and triggered the civil war in the 90’s. It was also the moment when many people, in their slim options for a better place, fled the country with whatever they had in overcrowded boats just to be rejected back or die in suffocation. This also marked a turn in policies against refugees and people in need. But as Ypi says, “failure is the shore from which we sail: not the port where we arrive.” Ypi teaches at LSE a course on philosophy in socialism. I met her in one of her book tours and I was fascinated by her questions on dignity, freedom, identity and philosophy. This is her first book and it brings so much learning to those who have emigrated from countries in crisis, or those who face the consequences of accepting a greater lie from the state: the illusions of nationalism. Her writing strikes me hard because I myself am an immigrant and, truly, no one wants to be an immigrant. I remain an apprentice for the history of Eastern Europe and Balkan countries and this is a book I’d highly recommend to fit in that puzzle.

Indignity: A Life Reimagined by Lea Ypi - This book reads like you’re on a movie set, crossing different realities and historical figures in a communist nation and its remnants in the present. In her first book, Free, Ypi explored how “biographies” became weaponised in post-war Albania and served as surveillance tools under communist rules: the last names, race, parents’ occupations, one’s own identity. Freedom, she argued, meant resisting this determinism while preserving one’s moral integrity. In her new work, Indignity, she is surprised by a picture on social media of her late grandparents happily honeymooning in the Alps in 1941, during the Second World War. And while being criticised by random online users, she also faces unsettling questions—growing up, she was told records of her grandmother’s youth were destroyed in the early days of communism, how is it then, that this picture prevailed, and was preserved in government records? Moreover, how can she defend her grandmother’s dignity against these comments? Ypi then makes an investigation beyond boundaries, reconstructing the past and building a fictionalised story about her ancestors who were closely tied to political figures, while grappling with the fragility of truth and the cost of decisions made many decades ago. One wonders, then, whether dignity depends on external recognition or on an inherent quality simply because of who we are. Does it require us to be alive, or rather, is it immaterial, beyond life and death? I became very fascinated by her philosophical reflections on the trade-offs we make to preserve our dignity—do we sacrifice dignity when we surrender independence? Or is there dignity in choosing dependence? Do we build dignity through the words we use to define ourselves, or do those words chain us to fictions?

I’d love to hear your thoughts on these ideas. The best books you can read come to you through word of mouth, so if you know good titles that relate, please share them! If any of these resonate with you, pass them along.