The Moment

Amor Fati.

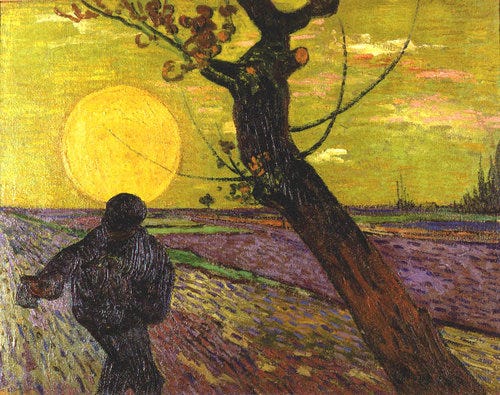

The moment when, after many years

of hard work and a long voyage

you stand in the centre of your room,

house, half-acre, square mile, island, country,

knowing at last how you got there,

and say, I own this,

is the same moment when the trees unloose

their soft arms from around you,

the birds take back their language,

the cliffs fissure and collapse,

the air moves back from you like a wave

and you can’t breathe.

No, they whisper. You own nothing.

You were a visitor, time after time

climbing the hill, planting the flag, proclaiming.

We never belonged to you.

You never found us.

It was always the other way round.

- Margaret Atwood

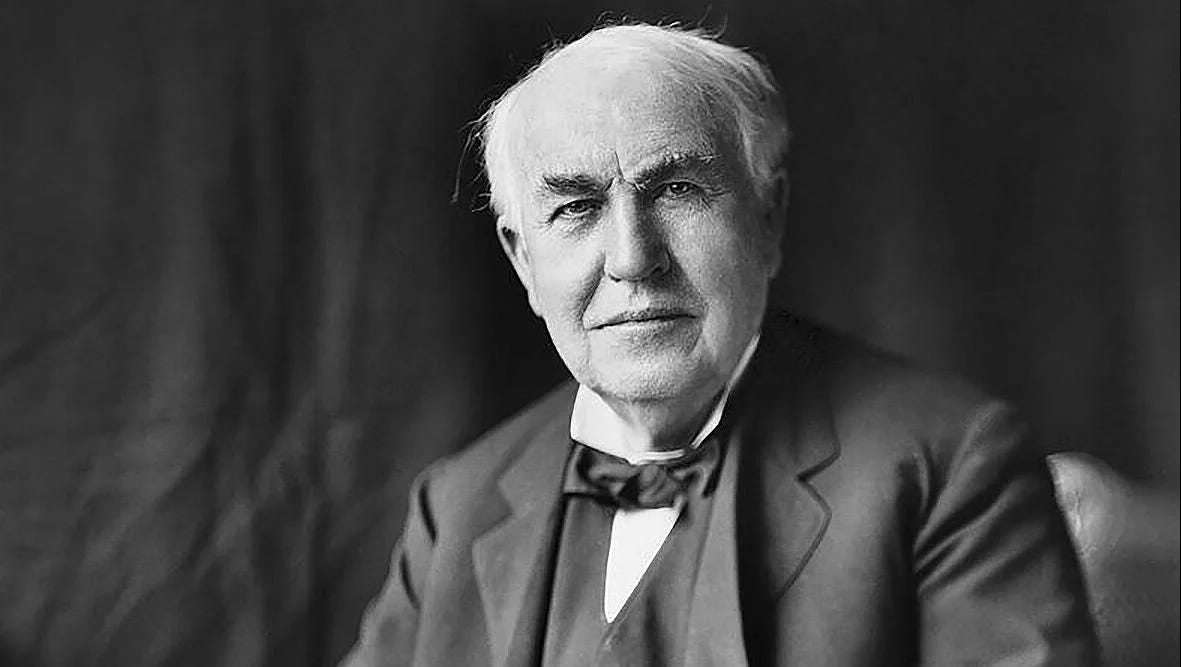

By his mid-60s, Thomas Edison was a very successful man. With 1,093 patents, he was a legend.

Western Union became his most prominent client and, at some points, his greatest foe, when he improved the telegraph to speed-transmit messages over long distances, one of his first inventions that carried over the years.

The world turned upside down with his invention of the phonograph while hearing sounds from a device.

He spent countless nights in his laboratory chasing the right filament to finally invent the lighting bulb.

He changed the construction industry, making significant improvements to cement production.

Storage batteries, electric generators, the first power grid revolution in New York City, the first attempt at motion pictures.

The man was unstoppable and full of ideas. “There’s no such thing as an idea being brain-born,” he said once. “Everything comes from the outside. The industrious ones coax it from the environment. The ‘genius’ hangs around his laboratory day and night. If anything happens, he’s there to catch it; if he wasn’t, it might happen just the same, only it would never be his.”

His obsession with the laboratory was so real that he built his house near his work in Menlo Park, New Jersey.

And so it happened that one of those nights, he decided to return home early, and shortly after dinner, a man came rushing into his house with urgent news: A fire had broken out at Edison’s research and production campus, which was a few miles away, in his second location.

His son Charles was devastated by the horrors and hopelessness of the scene. Desperately, he asked where his father was and finally saw Edison walking slowly into the yard, calmly and contemplatively.

“Where is mother?” Edison asked. “Get her over here and her friends too. They’ll never see a fire like this again.”

Charles, astonished, lamented it all, and without understanding his father, he pointed to the incalculable loss, to which Edison replied, “It’s all right. We’ve just got rid of a lot of old rubbish.”

A crowd of 10,000 people had gathered to watch the fire. A significant portion of his laboratory burned. Years and years of invaluable items, records, and inventions were turned to ash. Numerous firemen and volunteers came into place to help; one Edison worker was killed.

We imagine a man like Edison, at the pinnacle of his career, seeing such a fire burning his life work and thinking to ourselves: What should he have done? Be desperate? Cry? Quit and go home? No, Edison said, this re-energised him, “I am sixty-seven, but I’m not too old to make a fresh start.” he said, “I’ve been through a lot of things like this. It prevents a man from being afflicted with ennui.”

Within about three weeks, the factory was partially back up and running. Within a month, its men were working two shifts a day, creating new phonographs and inventions that the world had never seen. Edison again worked with furious energy, as in his youth. Despite a loss of almost $1 million ($31.5 million today), his team built up to generate nearly ten million dollars that year (Over $300 million today).

Edison's story reminds us of what Margaret Atwood exactly describes in her poem:

That you own nothing.

That we are just passengers in this long voyage.

That sometimes, the air will just move back from you like a wave. And you won’t be able to breathe.

That at some point we will face the world turning back on us. But that it is on us, like Edison, to turn back by changing what we must do into what we get to do.

“My formula for greatness in a human being is amor fati:” said Nietzsche, ”that one wants nothing to be different, not forward, not backwards, not in all eternity. Not merely bear what is necessary, still less conceal it… but love it.”

Amor Fati. To love what ends up happening.

In philosophy, it is described as learning how to die, splitting one’s individuality and passions to see things from the perspective of what really matters.

For Plato, training for death is a spiritual exercise that consists of changing one’s point of view. “He who has already tasted the immortality of thought cannot be frightened by the idea of being snatched away from sensible life.”

For the Epicurean, believing that each day that has dawned will be your last will give you an infinite value to each instant.

But in a world where we are just visitors, and most things are fluent, what should we focus on instead? Philosophers invite us to constantly distinguish three acts from the soul: our judgement, our desires, and our inclinations or impulsions.

On judgment, to be indifferent towards indifferent things. To understand the value of virtues and recognize moral evils.

On desires, to distinguish between the ones natural and necessary, those which are natural and unnecessary, and lastly, the not natural and not needed.

On impulsions, to focus on what you can control. And to do so for the good of you and others.

This is not to say that the good will always outweigh the bad. That despairing is not the response we need sometimes. And that when the world burns on us with all our inventions, we don’t need to struggle with it. Instead, this is saying that there is always some good in our circumstances, and even more, in some cases, that we can be reborn like a phoenix out of the ashes.

As we think about our actions, what are we facing today that needs a different perspective?

Sources

[1] The Moment - Margaret Atwood

[2] Thomas Edison - Matthew Josephson