The Real Wealth Nobody Talks About.

You are very aware of how much you've changed in the last twenty years. Sitting, walking, hearing, watching, minute by minute, you see your identity, friends, clothes, name —and you are. You are smarter, wiser, you have your beliefs about things in life have evolved, and that's true for most people.

But also most people, you included, may ask, who will you be in twenty years? Mostly, the answer is the same person you are today. There's always this belief that I have grown so much in the past, but you’re done growing.

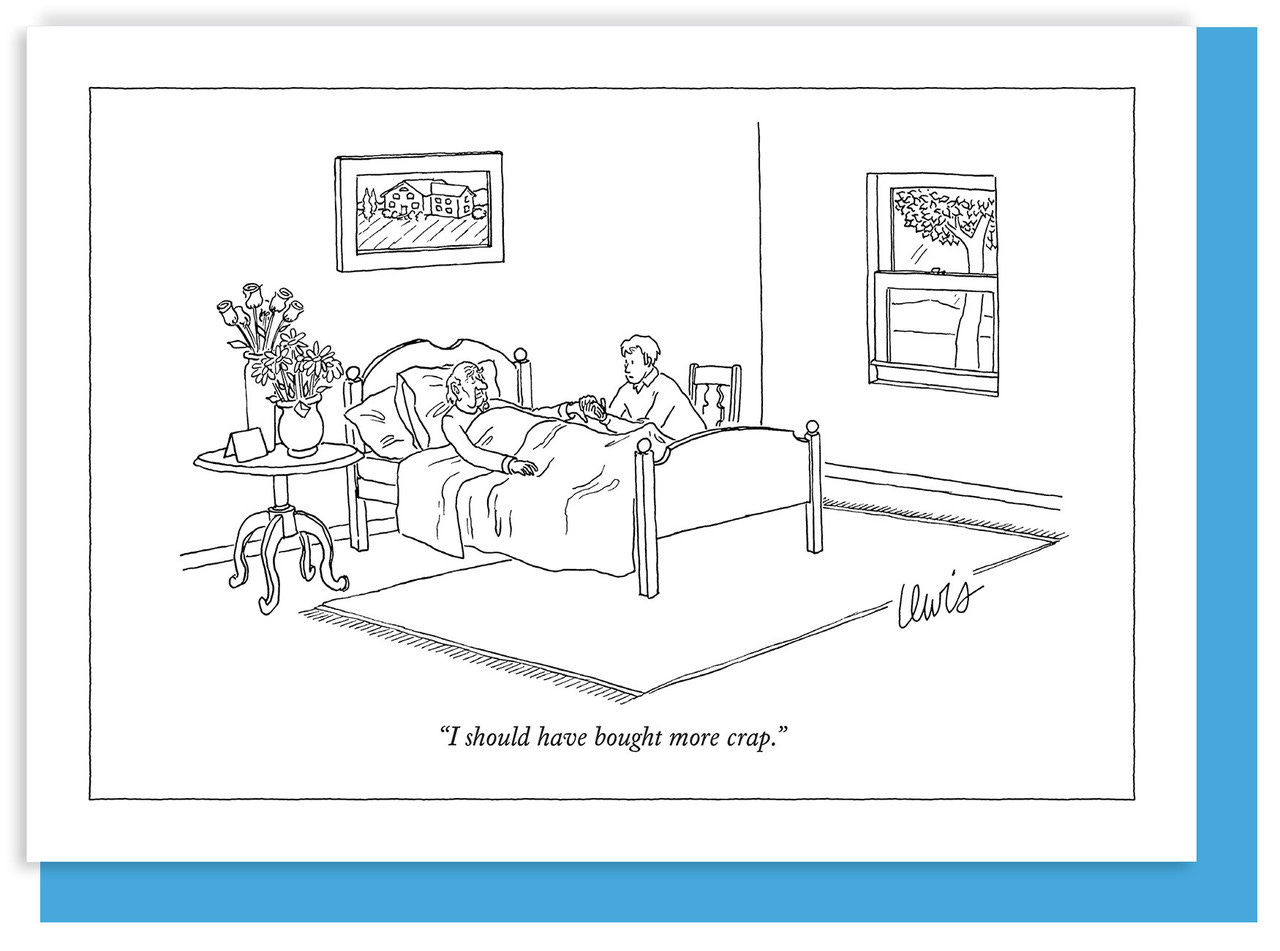

In psychology, this is called “The End Of History Illusion” (EOHI), and it’s bad, really bad. We underestimate what life brings us through in our values, preferences and personalities in the future. Yet, we make decisions overestimating our ability to see the next five years of our life (the classic interview question), and sometimes we end up working just to buy a lot of crap.

Humans biologically and professionally decline with age. After studying a century of Nobel winners and major inventors, the economist Benjamin Jones concluded that the likelihood of a major discovery increases through one’s twenties and thirties and declines dramatically in later life.

We might not be inventors, but we can count how many years we have before we stop assuming an unlimited life and ability to read, analyse, debate and solve novel problems. The psychologist Raymon Cattell calls this fluid intelligence. The sort that, once it peaks, goes down in your forties, fifties and sixties.

I remember peaking in different stages of my life for a work promotion or recognition on full merit. Top skills, hard work, long hours, risking health issues or relationship decay. Consequences happened, but I left the blinkers on because fluid Intelligence is addictive. It brings success, feeds the ego, and helps you feel “valuable”—an illusion of feeling better than others that, with time, we lose in race.

Our environments and social comparisons can easily lead us in the wrong direction, which makes us want more.

More fancy watches.

More latest phones.

More bigger houses.

More social media experiences.

More, more, more. The go-go years. The addiction of seeing it happen. Friendship groups are built around this. The big city life has changed in consequence. Mental health issues have tripled as a result. Our feelings get numb. The chase for peace gets lost. Drugs and medicine show off.

In his book Die with Zero, author Bill Perkins compared it energy-wise by saying that a person making $40,000 per year might be making more per hour than someone earning $70,000 per year. If being richer costs you more in terms of your life energy—the cost in time of a long commute to the city, the cost of the kinds of clothes you need for this high-status job, and of course the extra hours you have to put into the job itself—who is poorer at the end? Sometimes, being rich can leave you less time to enjoy the money you are earning.

Worse, the agony of decline at a later age is directly related to the prestige achieved and the emotional attachment to that prestige. By retirement, unhappier are those who have chased power and achievement in their professional lives. So you might assume the opposite is also true; if you have low expectations and no attachments, you end up more satisfied, but not quite.

Where does that leave us? Fortunately, says Raymond Cattell, fluid intelligence has an opposite, crystallized intelligence. It’s defined as the ability to use our cumulative learnings and overcome events in life. The marks you did, the pains you experienced. In other words, this intelligence is the real wisdom that peaks when you get older. It helps you become an elder and not an elderly.

I am not saying you don’t aspire to be rich. I am saying that you should be conscious about your abilities and addiction to do so because it will all be an illusion in your older years.

This is urgent: change your lenses or buckle up for your ambitions. For the record, research shows that among the top 10 richest people in the world, there are about 15 divorces accumulated.

While the phrase “money doesn’t make us happy” was likely said by a rich person, it’s also true that this person may have never understood why they needed the money in the first place.

On the contrary, in our quest for material gains, the greatest wealth becomes the wealth of the mind and the people with whom we share our lives. Unhappy is he who needs success to be happy.

In his book 30 Lessons for Living, Karl Pillemer interviewed over one thousand people over the age of sixty-five to understand what makes them happy, and this is what they didn’t say,

No one said that to be happy you should try to work as hard as you can to make money to buy the things you want.

No one said it’s important to be at least as wealthy as the people around you, and if you have more than they do it’s real success.

No one said you should choose your work based on your desired future earning power.

The crystallized intelligence concept points to the same ideas Cicero had on old age about two thousand years ago: That actually, it is our greatest duty to accumulate life and enrich others by creating a better worldview. That it is our role to move from problem-solvers to mentors, advisers and teachers. That the pursuit of moral virtues is the highest goal in life.

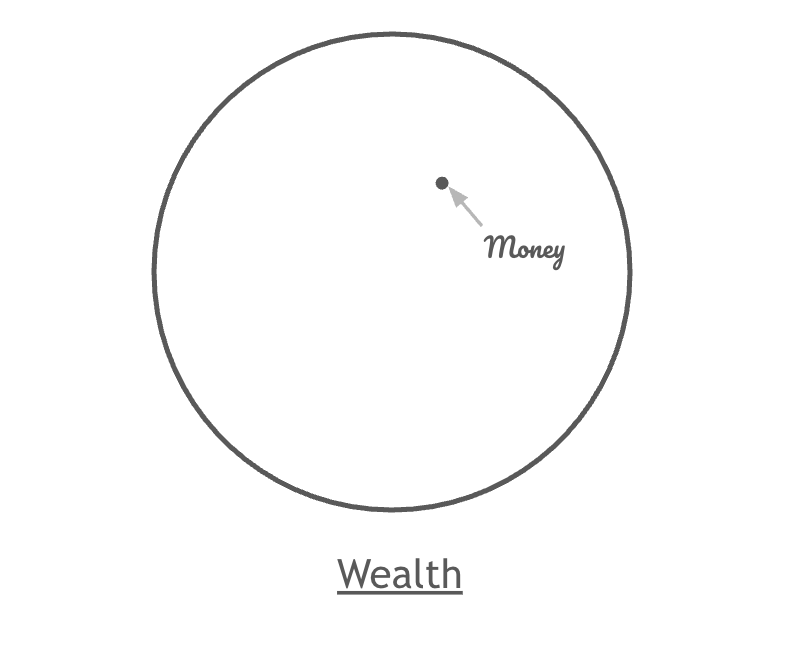

By focusing on our crystallized, we set boundaries for what is fluid. Seneca pointed out that the greatest wealth is a poverty of desires. That the greatest empire is within us.

Yet, here we find ourselves still assuming that in the next twenty years, we will be able to use our phones the same way.

Walk the same way.

Speak the same way.

Think the same way.

We defend our long-term holds and sometimes take actions that affect us down the road.

We are inconsistent with what we say and what we do.

It’s a dangerous habit. And as Cicero saw it, we can also act on it. Thinking about the inevitable end has a way of putting everything into perspective.

When George Lucas was a teenager, he almost died in a car accident. He decided, “Every day now is an extra day.” At the peak of her career, Joan Didion pointed out that she constantly read obituaries, as it helped her shape perceptions of life and death in her essays. Austin Kleon said that he spends time in the morning reading obituaries as he brews his coffee. “Thinking about death”, he says, “makes me want to live.”

Seen in this way, reading obituaries is not thinking about death; they are about life, in finding how impactful people can be; in seeing heroes without a cape.

In his book Road to Character, David Brooks makes this distinction by comparing Résumé Virtues to Eulogy Virtues.

Résume Virtues are professional and oriented towards earthly success; these are the ones that you lose your edge on later in life. Whereas Eulogy Virtues are ethical and spiritual and require no comparison. Each great wisdom or religious literature has its list of main virtues to drive communion,

In Stoicism these are courage, discipline, wisdom and justice.

In Christianity they added three more: faith, hope and love.

In Buddhism these are generosity, moral discipline, forbearance, vigour, meditation, and wisdom.

In Islam these are kindness, forgiveness, honesty, generosity, gratitude, justice, charity, and patience.

In Judaism these are justice, truth, peace, love, compassion, humility, charity, ethical speech, and self-respect.

Every philosophy has its own old truths. Those virtues whose meaning and impact will never be exhausted by the generations of man. Old people have an edge over young people by virtue of their life experiences, but only if we have the right lenses. To calibrate, Arthur C. Brooks in his book From Strength to Strength, puts it well by saying “People say to live in such a way to be always ready to die. I would say to live in such a way that anyone can die without you having anything to regret.”

Visiting my parents house, I remember sitting with my mom in the living room, overwhelmed with my nephews and nieces running around, playing and screaming, as I noticed that half of the decoration cushions were on the floor and souvenirs were missing a few pieces. I turned to her and asked whether she’s become more stressed in consequence, “Son, why would I be stressed about these souvenirs if at the end of the day we don’t take any of these with us?” she replied and continued, “what matters are the memories that they build in this house and that they will take to the future.”

There is nothing more wonderful than looking back on your life by seeing your room collections and, instead of the latest TV set or Black Friday gadgets, replacing them with the pictures of you and your friends and family on those trips, dines, Sundays, barbecues or walks together. For my parents, it is about the memories they will be able to build for future family generations.

As we realise that our most significant impact is actually around others, the greatest lesson is to focus a little bit more every day on what matters in the future.

Build memories that matter and share them with others.

Gather your learnings and prepare your teachings.

Experience more wisely.

Do the material, but get yourself training for the long run.

Make the time to realise,

That the watch you bought is actually to measure your life with others.

That the latest phone you’ve got is to take pictures and videos of moments that will not return.

That the bigger house is to invite people and friends over and share life with.

That social media is more about connecting and less about competing.

Arthur C. Brooks does an incredible exercise to start accumulating real wealth. It is as simple as recognising and reaching out to those you like and finding those you love. Write down the things that you want from them and then ask:

Am I investing in their lives? Am I putting my time, energy, affection, expertise, and money into developing these assets and qualities? Am I modelling them with my own behaviour?

It is finally the wealth you can’t count that matters, and you need to start soon. As an old Chinese proverb says, “The best time to plant a tree was twenty years ago. The second best time is now.”

Sources

[1] From Strength to Strength - Arthur C. Brooks

[2] Die With Zero - Bill Perkins

[4] Farnham Street - 30 Lessons for Living - Karl Pillemer

[5] A Few Laws of Getting Rich - Morgan Housel