Why Your Best Friends Keep Disappearing.

The hidden psychology behind relationship patterns.

In The Banshees of Inisherin, two lifelong friends sit in an Irish pub in the middle of nowhere. Colm (Brendan Gleeson) decides their friendship is over, while Padraic (Collin Farrell) doesn’t understand why and desperately tries to salvage their friendship.

“Now I’m sittin’ here next to you, and if you’re goin’ back inside, I’m followin’ you inside, and if you’re goin’ home, I’m followin’ you there, too.” Says Padraic in almost a falter tone and continues, “now, if I’ve done somethin’ to ya, just tell me what I’ve done to ya. And if I’ve said somethin’ to ya, maybe I said somethin’ when I was drunk, and I’ve forgotten it, but I don’t think I said somethin’ when I was drunk, and I’ve forgotten it. But if I did, then tell me what it was, and I’ll say sorry for that too, Colm. With all me heart, I’ll say sorry. Just stop running away from me like some fool of a moody schoolchild.”

To which Colm, staring directly to Padraic eyes and in a very still tone responds,

“But you didn’t say anything to me. And you didn’t do anything to me. I just don’t like you no more.”

“You do like me.”

“I don’t.”

“But you liked me yesterday.”

“Oh, did I, yeah?”

“I thought you did.”

As the conversation goes on, Colm decides to withdraw from Padraic (See Scene Here). And the next day, Colm points out clearly how he has decided to move on from their friendship because he needs to “spend the time I have left thinking and composing,” not wasting it away in consistent aimless chatting like two hours talking “about the things you found in your little donkey’s shite that day.” To which Padraic declines and argues that is indeed relevant.

This unusual dialogue is an anatomy of how relationships die. Despite being in a remote place of Ireland during the Irish Civil War in 1923, it shows how one person evolves, the other stays stuck, and neither knows how to bridge the gap.

It’s relationship chaos, and it’s not my intention to make you judge. After all, I would also get tired if someone is talking non-stop about their pet’s crap for two hours. Rather, it’s about recognising that we’ve all heard or said the excuses: “This is the way I am.” “They are not a positive friendship to me.” “I never learned anything different.” Understanding why we’d rather stay stuck than do the hard work is the key to building relationships that last instead of constantly starting over.

After making mistakes and bringing unintended consequences.

After dozing off on solutions and letting time pass.

After losing our way to where peace was present.

Then we tell ourselves our situation is unique. That no one else would understand. That we're ethically right and they're not. This thinking isn’t just wrong, but also dangerous. It prevents us from seeing the patterns that destroy our relationships.

Moreover, psychologists have found that our biggest regrets aren't about chances we took—they're about relationships we abandoned. It's been said that secrets usually involve things we’re ashamed of, and one of those seems that often we return to our memories and regret actions that triggered a withdrawal.

But why would you? Like Colm, maybe in a random place in Ireland that has less than a hundred people, you might have found a better path to your passion and identity. You have moved on. Yes — life may have brought other wonderful friends, maybe a new partner. Yes — you might also have moved on from them into new ones. Yes — a damaged relationship can mean significant pain and sometimes the best thing is to be apart. But how do we know when it is healthy to grab opportunities to recover someone? How do we avoid future regrets?

I’d rather take a step further back and ask, how do we start a relationship without the need to toss and likely “recover” later on? Does it have to do with “evolving” as a human being and finding new people along the way? Why do we need to normalize to move on from people so much?

The good news is that you don’t need to, but it is hard not doing so.

Different research points out that it’s a complex but straight result of our childhood and later self-awareness. Starting from accepting that relationships are unavoidable, that people are born into them—with parents, with surroundings, with ancestors—and that they create us in our formative years. Hence, the more you know about how your caregivers impacted you, the more prepared you will be to face your relationships with everyone.

Even more, having social connections is one of the strongest determinants of our happiness. It expands our identity and it helps us build perspective. Loneliness can be more fatal than a poor diet or lack of exercise, as corrosive as smoking fifteen cigarettes a day.

In other words, no matter how much you believe that you’d rather be alone, you’re naturally not made for loneliness. Opposite to that, friendships can literally save our lives. And most of us don’t know how to be involved with people because we don’t know who we are and what we want.

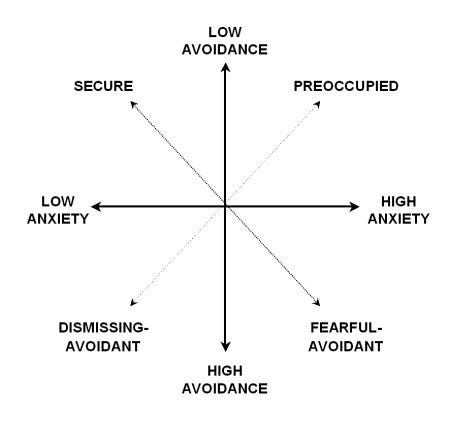

But even as you change, your relationships can remain strong, especially those with friends. To understand how, we have to learn how each of us see relationships in general. Psychologists call this attachment theory, and generally there are three types (there’s also a test at the end of this essay if you’re curious about yours),

The avoidant: Raised by emotionally distant parents, they learned that closeness equals danger. These children lack opportunities to explore the world and are confined within the realm of restrictions. In making life choices (moving out, entering new worlds, making big decisions), they’d often find that others want to pull them into more closeness than what’s comfortable. They tend to end relationships more frequently, or suppress loving emotions. For them, It is important to maintain independence and self-sufficiency, and often prefer autonomy to intimate relationships.

The ambivalent (or anxious): Raised in chaos, they learned that love is unpredictable. These children are more fearful than other children. They are more likely to perceive threats. Their life choices are situated with fear first. Relationships tend to consume a large part of their emotional energy. They tend to act out and say things that they later regret. They would interpret calmness in a relationship as a lack of attraction because they don’t know what calmness is.

The secure: Raised with consistent love, they learned that relationships are safe. They give others the benefit of the doubt and work through problems instead of running away. What kids need most are safety and exploration. They need to feel loved but they also need to go out into the world and to take care of themselves. Despite the fact that parents don’t have to be brilliant psychologists to succeed at this, many still underestimate the need to provide stable and predictable rhythms to a child’s life. They don’t get easily upset over relationship matters. A secure person can drive most relationships into stability, no matter if there’s a rollercoaster of a type on the other side.

To break down types of relationships on a high level, author Angela Chen reveals that we feel romantic (heady passion and idealisation of someone), sexual (desire to have sex with someone), or platonic (appreciation and liking toward someone) separately.

This could mean three things. First, most secure and stable people are out of the romantic market already. They are already likely engaged in a relationship. So if you are looking for your meaningful other, there is a higher chance that you will encounter anxious or avoidant people. Second, you can bring stability to most of these relationships by having at least one of you be a secure or self-aware person (it can be you!). Third, an underestimated point is that the same attachment styles apply not only to romance but also to our friends (platonic).

In her book Platonic, author Marisa Franco points to the secure or self-aware types as “super friends”, who are people expert at making and keeping friends. With relationships that are also closer and more enduring, research finds that these people also flourish in their personal lives, with better mental health, open to new ideas, harbour less prejudice, are satisfied at work, and are viewed more positively by others. They are also less regretful and remain calm under pressure, better able to withstand life's punches. They are even less likely to have physical ailments like headaches, stomach troubles, or inflammation.

Super friends don’t seek revenge for other people’s actions in their relationship. Rather, they see most negative events in the relationship like accidents. They are forgiving and give the benefit of doubt, reassuring that everything is okay. They internalise that they are connected to others by their history of abundant love with their caregivers. Making a mistake, they would respond differently:

Did you say something hurtful to them? Probably unintended, but it's good to clarify.

Did you miss the special event? You might have something more urgent or forgotten, worth having a call about it.

Did you act wrong? You likely were not aware, better to show by example.

Franco points out that, aside from their secure attachment or self-awareness, super friends not only know what they can offer, but they also recognise that not everyone can be a best friend. They understand that friendships take work and initiative. But also that there are people from whom they should expect less (such as a two-hour talk about a donkey’s stool). They kindly communicate what they need from others, and ask and clarify how they can better support. They understand that the goal is to focus on what feels most fulfilling about each relationship.

Super friends are also authentic, unique to themselves and to the friendship. They live in the middle, far from bluntly expressing what they want, think or feel (that’s rawness), and also away from saying anything at all (that’s withdrawal). They act in a way that balances others’ needs, responding without reacting, setting boundaries, care, space. Acting opposite to a super friend, we could trigger some of the opposite behaviors seen as follow,

If we can’t tolerate feeling inadequate, we may get defensive in conflict.

If we can’t tolerate our anger, we may act passive-aggressively or aggressively.

If we can’t tolerate rejection, we may violate friends’ boundaries.

If we can’t tolerate anxiety, we may try to control our friends.

If we can’t tolerate guilt, we may overextend ourselves with friends.

If we can’t tolerate feeling flawed, we may fail to apologize when warranted, blame others, or tell people they’re sensitive or dramatic when they have an issue with us.

If we can’t tolerate feeling insignificant, we may dominate others.

If we can’t tolerate sadness, we may avoid friends who need support.

If we can’t tolerate tension, we may withdraw from friends instead of addressing problems.

If we can’t tolerate feeling insecure, we may brag about ourselves while putting down our friends.

If we can’t tolerate feeling unliked, we may act like someone we’re not.

It is a revelation of our identity to be part of any of these. But it is a lack of self awareness to continuously repeat them. It is worth noticing that over 2/3 of people remain with the same attachment style throughout their lives, so the secret sauce is in understanding yourself first before diving into others. By understanding your weaknesses, learning how to be loved, and taking care of yourself, you could select and achieve your stability goals towards others.

Painfully, on the other hand, sometimes we need to fail with someone to realise where we are in the attachment theory. Or even worse, that by trying to become secure, you would still not get reciprocity on the other side. Sometimes, the response might also be to distance and move on. But when you make a mistake, realise that those are where learning sits, where growth starts. Without mistakes, you would have missed your gained awareness, the people that currently surround you, and your ability to be human in this journey. And if you have an opportunity to fix relationships, take it. I think it is wonderful to always have an opportunity to be brave and honest.

The attachment type test

Authors Amir Levine and Rachel Heller wrote one of my favorite books on relationships, Attached, and has a great test to identify your attachment style to start with. Luckily I found the PDF online and I am also attaching it here. I would strongly urge you to do this test, the goal is to check the small box next to each statement that is TRUE for you. (If the answer is untrue, don’t mark the item at all.) The more statements that you check in a category, the more you will display characteristics of the corresponding attachment style. Category A represents the anxious attachment style, Category B represents the secure attachment style, and Category C represents the avoidant attachment style.

How easy it is to hear about great relationships from others and say “I wish I could have a relationship like that.” Rarely you’d find this option on the table but the answer is that you can be that friend right now. Reciprocity commands in relationships, initiative commands reciprocity, it’s never too late to start.

Sources

[1] Platonic: How Understanding Your Attachment Style Can Help You Make and Keep Friends by Marisa G. Franco PhD

[2] Attached: Are you Anxious, Avoidant or Secure? How the science of adult attachment can help you find – and keep – love by Amir Levine (Author), Rachel Heller (Author)

[3] The Social Animal: The Hidden Sources of Love, Character, and Achievement by David Brooks

Tan hermoso

Is always good to read you :) Thanks for being one of my super friends!