Your Greatest Gifts.

A world we cherish.

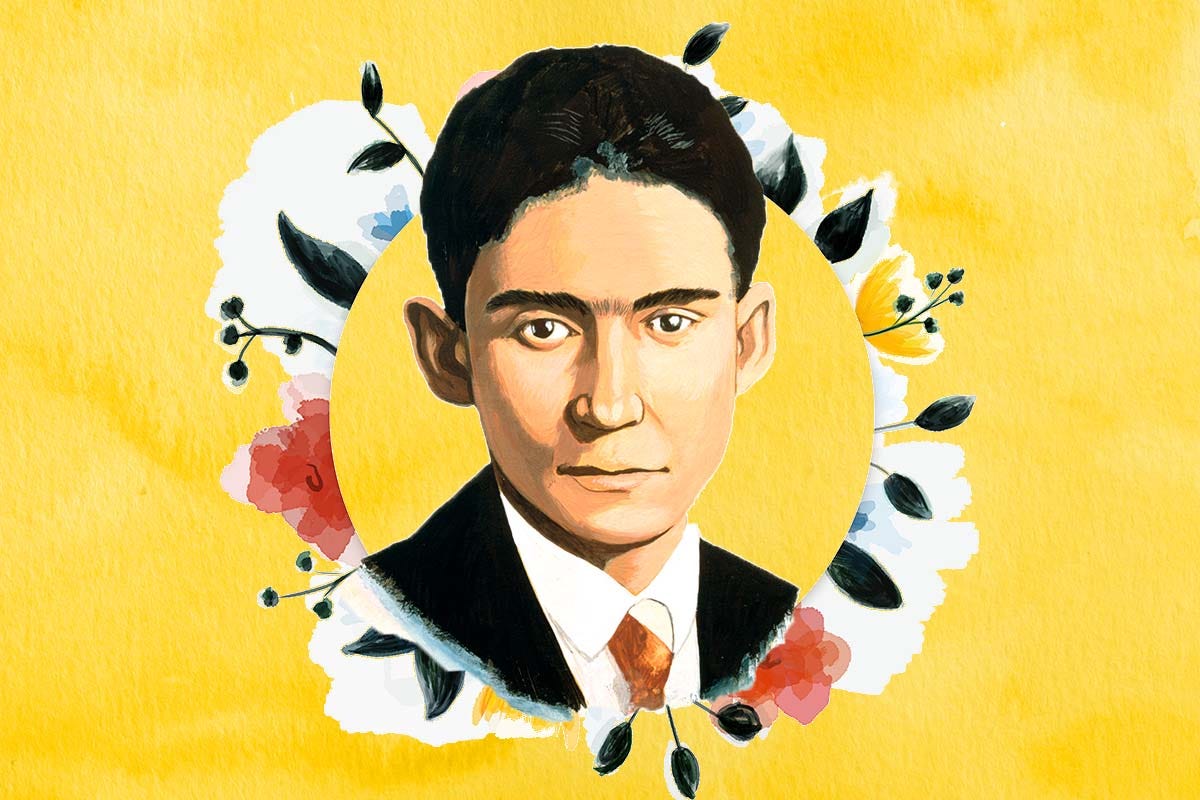

History describes him as one of the great European novelists of the twentieth century. Yet at forty, ill, the lawyer and reluctant writer Franz Kafka labelled his life as a necessary torment, poignant of the things that went troubled.

Troubled relationships.

Troubled childhood.

Troubled dreams of marriage.

Troubled stress and results of illness.

Troubled frustrations with his career, finding time to write more, but also troubled finding value in his writings.

It was such his torment that, by turns, he found himself drowning in loneliness, enraged by distraction, physically fatigued and pained by the tuberculosis that would soon take his life.

Self-critical and insecure, most of his works ended up being published post-mortem.

But this time, he was visiting Berlin to see his partner. In his self-doubt and constant comparison, he is surprised by a tearful little girl who lost her favourite doll. Feeling her pain, he tries and fails to help find the doll, then tells the girl that the doll must have taken a trip. But he also says that he casually is a doll postman, that his role is to send word from dolls around the world, including hers.

They meet again the next day, and Kafka brings the girl a letter. “Don’t be sad,” says the doll in the letter. “I have gone on a trip to see the world. I will write you of my adventures.”

After that, Kafka gives the girl many such letters. The doll is going to school and meeting exciting new people. Her new life prevents her from returning, but she loves the girl and always will.

At their final meeting, Kafka gives the girl a new doll with a letter attached. The letter says, “My travels have changed me.”

The girl cherishes the gift for the rest of her life.

Time later, the girl finds another letter stuffed into an overlooked cranny in the substitute doll. This one says: “Everything that you love, you will eventually lose. But in the end, love will return in a different form.”

In the same way that Kafka revolutionized the world with his fictional writings, he also did to us with the love story of this little girl.

Yet, he suffered greatly doing so.

Before he passed away less than a year later, he reviewed his unpublished writings and told his partner Dora, “All these attempts are just attempts. The real word has not been spoken yet."

A century later, we still read Kafka’s works and novels; he helped in the evolution of fiction literature and transformed the lives of many new authors. Essentially, he made the world a better place. However, we could argue that what made Kafka’s writing and personality special was his troubled life.

Often, the glorious end state of our lives is anything but glorious. Less expected, our struggles can become the source of our ability to help others.

Often, the loneliest people are the ones who make the greatest friendships. They are so far away, so unsure where they belong, that once they earn this connection, they give it back genuinely to the universe.

Often, those who are heartbroken are the ones who give the greatest love if they are granted the occasion.

Often, those who are frustrated but are unconsciously practising their dreams will make the most beautiful attempts and lessons when the space is settled once again.

But it is hard for human nature to see ourselves differently when this happens, not to compare ourselves with better attempts. To not self-sabotage.

Soaking ourselves in our comparisons is at the heart of unhappiness.

Yes, we have to start with someone for reference. We see that big personality. Insert the parent, professional, sibling, friend, artist, or athlete here.

And then we try. We try hard. We do our best. We play to win. We jump the highest. Like Kafka, we might write in the evenings and weekends, but then we see someone better. A better writer, mother, manager, human being. A better story. A better way to find unhappiness.

At the heart of this trouble, we face the cult-identity issue. Our beliefs form the fabric of our identity. We motivate ourselves to keep our beliefs intact to achieve our goals, and we ignore the circumstances of our realities. We want our identities to be consistent until we reach the highest position. Targeting the north star and the achievements that await. The big ones. The ones we didn’t get.

Kafka built his talent to make his life work last for generations. Maybe that also wasn’t enough for him, and perhaps you won’t have enough of that work to realise it either.

But also often, beauty lies in the way. Not in the experiences you didn’t create yet or never at all, but in the lives you helped change when you were in the process.

A friend of mine in his fifties comes from a conservative family. He is the oldest of his siblings. Coming from a hard childhood and a tough family legacy, he told me that he lamented his wealth status during his lifetime. The years passing while he works hard to set the structure right for his kids without making much money in return. To not repeat the mistakes that his parents made with him, leaving so much behind as a result.

I reckon the contrary. His struggles and pains in life helped transform his generational reality, and that might be his greatest gift.

Perhaps there is no fame or much material gain in the process.

Perhaps there is no recognition or celebration.

Perhaps circumstances were not the greatest to have one getting to the finish line.

Perhaps there is an unachieved dream.

Perhaps there was great suffering.

But ultimately, the greatest gifts you make come with trying.

Maybe it was the years just making a hard business work, the family you helped with a life advice, the marriage you saved, the example you showed to a kid, the letter you wrote, the conversation you had, the attention you gave to an issue. Maybe it was just listening to someone when was needed the most.

Moments that didn’t make a dent in the universe, but moments that maybe impacted someone’s life, and that’s worth the universe.

Some of my favourite bands don’t have many followers. My favourite places in the world are the least famous ones. The stories I remember the most include things other friends told me in those instances. They wouldn’t know this because I haven’t shared these points enough. They are not popular humans, and some might live lives saying that, in general, their landscape wasn’t enough. Yet these gifts have secretly changed my life. I constantly search for them. I praise the world for them.

In my friend’s case, he could lament how his life turned out, but a different legacy is already taking shape. A new and better generation will come his way, turning the way he fought for. It may take the kids ages to realise this. Perhaps they won’t realise it at all. However, we don’t need credit from anyone; we only need to cherish it ourselves.

Sources

[1] Bittersweet: How Sorrow and Longing Make Us Whole - Susan Cain

[2] Franz Kafka, An Unusual Writer - Diego Mattei

[3] Kafka on Friendship and the Art of Reconnection - Maria Popova